NOTE: The following case examples were developed as part of Subpart A Subcommittee (SAS) discussions toward an analytical framework for minimal risk. They are extracted here for consideration of illustrative cases, to supplement text recommendations already approved by SACHRP on 3/29/07.

Case I. Researchers interested in end-of-life decision-making propose to use an hour-long semi-structured interview to gather data from subjects who are recruited in a hospital cancer treatment center.

- The estimate of harm and discomfort of such a research intervention will depend on many factors, including who the researcher will interview, when during the course of a patient’s illness the interview is conducted, the qualifications of the interviewer, and others.

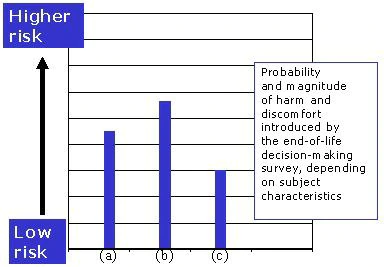

- The same semi-structured interview might be judged to cause significantly more distress in newly diagnosed patients with cancer or if administered to acutely bereaved family members than in a sample of patients who are previously diagnosed and are participants in a support group for terminally ill patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The same end-of-life decision-making survey is judged to introduce different risks in the group of (a) acutely bereaved family members, (b) newly diagnosed patients with terminal illness, and (c) patients in a support group for the terminally ill.

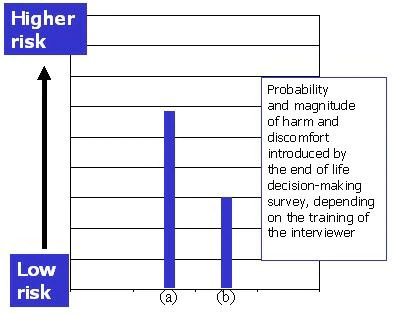

- The same diagnostic interview in the hands of a clinician experienced in working with the terminally ill can be expected to cause less harm or distress (it may, in fact, be therapeutic), than in the hands of unskilled interviewer (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The same “end-of-life” decision-making survey is judged to introduce different risks depending on the training and skills of the interviewer: the estimate of risk in (a) an unskilled research assistant, and (b) an experienced clinician.

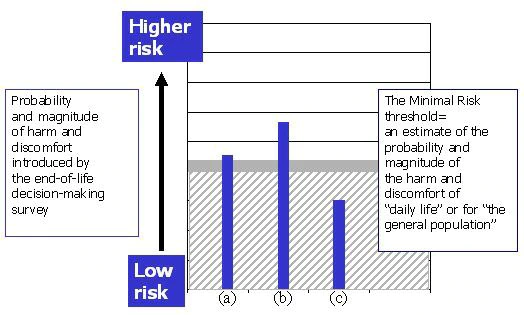

- The estimate of risks introduced by the research interview is compared with the estimate of harms and discomforts of daily life. In this case, the interview in newly diagnosed cancer patients or recently bereaved family members is seen as introducing more harm or discomfort than “the average person” might experience in daily life, or during the performance of routine physical or psychological assessments. Therefore, as proposed and in these populations, this study might be considered greater than minimal risk (Figure 3 bars (a) and (b)).

Figure 3. The same end-of-life decision-making survey falls above the fixed threshold and would be considered a more-than-minimal risk study in subject groups (a) and (b). In subject group (c) the study is minimal risk.

- In the group of patients who have spent considerable time in considering end-of -life concerns in a support group (Figure 3, bar (c)), the research is judged to introduce less harm or discomfort, given the subjects’ experience. For them, the harm or discomfort might be considered no greater than that of daily life for “the average person.” Therefore, this study in this population may be considered no greater than minimal risk.

Case 2. A cross-sectional study of memory and attention in cocaine dependent subjects and in healthy subjects with no substance use history involves a 3-hour battery of commonly employed neuro-psychological examinations.

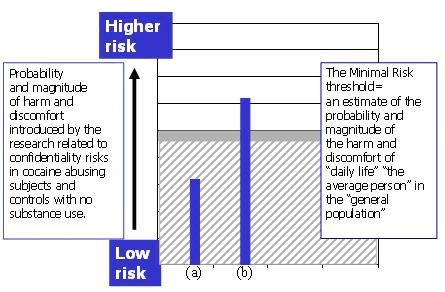

- The administration of the assessment battery to the subjects is judged by itself introduce no risks beyond those of daily life (or, specifically, routine evaluations) for “the average person.” Were the same study to be done, e.g., as a pilot, in the healthy control group only, the risk would be below the minimal risk threshold (Figure 4, bar (a)).

- However, the potential social, occupational and legal harms for cocaine abusing subjects if their study involvement were to be revealed are significant ones, given that they are actively using illicit substances. This risk is above the threshold of the risks of daily life (Figure 4, bar (b)).

Figure 4. The estimate of study risk for research subjects with no substance use history (a), fall at or below the minimal risk threshold. For cocaine dependent subjects (b), risks related to confidentiality in the study as proposed are judged to introduce significantly higher risks.

- The fact that risk of legal liability is part of the daily life of substance abusers is not relevant in the analysis of minimal risk.

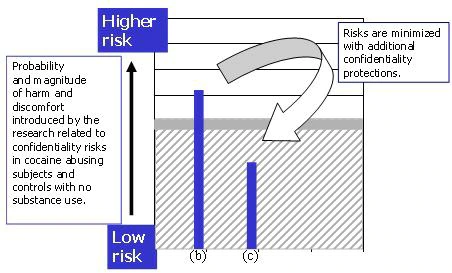

- If the study proposal were to include special protections regarding confidentiality, for example, obtaining a federal certificate of confidentiality, segregate and restrict the data set from access beyond the research group, pay the subjects by “untraceable” means, the study would likely be considered below the minimal risk threshold (Figure 5).

Figure 5. With additional confidentiality safeguards, the study risks for substance users (b) are minimized (c), and the study is now considered minimal risk.

Case 3. A study of immune response to treatment in adults with leukemia involves a series of three bone marrow biopsies over a five-day period. All subjects have had several prior bone marrow biopsies for treatment purposes.

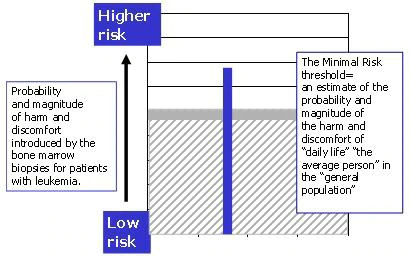

- While a bone marrow biopsy may be considered a risk of daily life for patients with leukemia, the minimal risk determination requires that we judge whether the risks introduced to these subjects by the research procedures are greater than the risk of daily life for “the average person.”

- While these subjects may be familiar with the procedure as part of their treatment, the biopsy does not cause less pain, or introduce a lower risk of infection or bleeding because of their experience.

- The fact that the subjects have experience with the procedure is not judged to reduce the harm, and the overall risk is judged to be greater than the risk of daily life (Figure 6).

Figure 6. While patients with leukemia may have experience with the bone marrow biopsy, this experience is not seen as lowering the main risks associated with the procedure. The risks of the research, for them, are considered greater than the risk ordinarily encountered in daily life for "average person" in "the general population".

Case 4. A study of social functioning in clinically stable outpatients with schizophrenia includes a comprehensive assessment of psychiatric symptoms and interpersonal relationships in a three-hour, interview-based assessment. A psychologist conducts the interview; the procedures are divided into three one-hour sessions with breaks.

- The interview assessment is lengthy and involves personal matters, and might be experienced by some as stressful, intrusive, or even upsetting.

- Given the experience of outpatients in mental health treatment, such an assessment is not likely to be experienced as intrusive or stressful as it might in subjects less familiar with psychiatric assessment.

- In the hands of a trained interviewer, any such harm will be further reduced.

- In this analysis, the background of these subjects as patients is seen as lessening their experience of discomfort in the interview. In this population, the interview is judged to introduce harms or discomforts that are no greater in probability or magnitude than that of “daily life” for the “general population.”

Case 5. A study of cardiac physiology involves non-invasive cardiac monitoring during an maximal exercise stress test. The study sample includes “older subjects,” age 65-80, all of whom have risk factors for cardiovascular disease, and medically healthy trained athletes, age 18-30. Subjects are screened for eligibility with a standard physical exam and medical history. The research procedures are monitored by a trained research assistant.

- The harms of the exercise stress test must be identified and estimated for the proposed subject samples. In this case, the risks of the study are likely to be significantly different in the two groups.

- If the study were to involve only younger, trained athletes, pre-screened for cardiac problems, the exercise stress test might be judged to introduce risks that are no greater than the risks of daily life.

- In the older group, a group that is more likely to have cardiac problems that are not identified by history or routine physical exam, the exercise stress test is judged as introducing risk that, in probability and magnitude, is greater than the risks of daily life. Since both subject groups are to be studied, and for one of those groups the research is greater than minimal risk, the overall study is considered to be greater than minimal risk.

Case 6. A study comparing two diversity sensitivity educational programs conducts pre- and post-intervention surveys of workers. A subset of respondents will be interviewed. The self-report survey topics include views of supervisory styles, stress, job satisfaction, and job productivity in several work environments. Identifiable subject data will be recorded.

- The “risks” of the intervention itself may be associated with the time commitment associated with survey completion and interviews (e.g. longer surveys maybe boring or take time away from work), but the main risks of the research include those relate to breach of confidentiality. For example, the estimate of the study’s risk will consider harms (e.g. loss of employment) that may occur should employee survey responses become known.

- Whether this study’s risks are judged to exceed the minimal risk threshold will depend on the workplace environment, the nature of the workplace studied, and employee characteristics. For example, a study involving lower rank or non-permanent workers may introduce a greater risk of retribution from supervisors if negative assessment of supervisory behavior becomes known. For any undocumented workers, the collection of demographic data itself may place such individuals at risk and research recruitment and participation may themselves be experienced as stressful.

- Whether this study’s risks are judged to exceed the minimal risk threshold will depend on how well the procedures for recruitment, data collection, and data storage safeguard subjects’ right to decline participation and how well employee responses are protected from inadvertent disclosure in the workplace.

- Study risks can be minimized, for example, by assuring that a subject’s decision to enroll (or not) remains confidential, by requiring that all data is coded and identifying information is removed, that links between codes and identifying information be appropriately safeguarded, and by explaining to prospective subjects the confidentiality safeguards in the research. So minimized, the study risks are estimated to fall below the threshold for minimal risk.

Case 7. A U.S. research team aims to examine community, social, and political crises as barriers to local access to foreign relief assistance. The study is to be conducted in several remote villages in a country in South Asia devastated by both the Tsunami of 2005 and persistent violent civil unrest. Focus groups and individual interviews will be used to gather data on individual and family access to relief assistance. Individual interactions with community leaders and relief organizations will be described.

- While focus groups are ordinarily considered minimal risk procedures, knowledge of the local context is critical to the proper assessment of subject risk. For example, group composition (e.g. including both men and woman) may itself cause considerable discomfort or breach local custom. Discussion of attitudes or complaints regarding the local authorities may be experienced as uncomfortable. Disclosure of this information within the focus group or unintended disclosure outside the group may place individuals at considerable risk for personal harm.

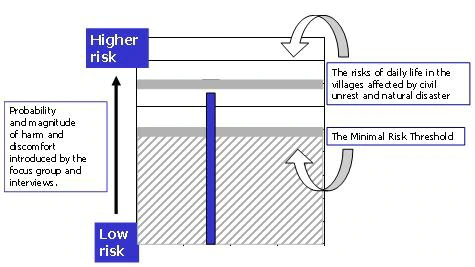

- The fact that these communities have been devastated by natural disaster and civil unrest—the fact that their “daily life” confers considerable risk from hunger, illness, and violence—does not alter the minimal risk threshold. We do not consider their circumstances as representing a reasonable background level of risk on which to base the minimal risk estimate (Figure 7). To do so would mean that the risk estimate even for studies judged to be greater than minimal risk in other settings would still fall below the estimate of background risk in this locale.

Figure 7. While the risks of the focus group fall at or below the estimate of risks of daily life in the villages affected by civil war and natural disaster, this is not the background level of risk upon which the minimal risk assessment is based. This study is greater than minimal risk.

- Therefore, we apply a fixed threshold. We also recognize that the local circumstances might confer additional vulnerability to the research participants. The same focus group procedures in a safer setting might fall below the minimal risk threshold.