SACHRP Recommendations Approved May 26, 2017

Sharing Study Data and Results: Return of Incidental Findings

Introduction

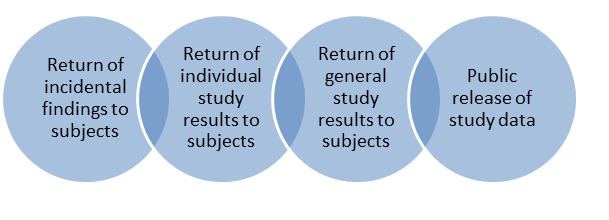

There is currently significant attention to the distribution of study data and results, both to the subjects who participated in the research and to the public at large. SACHRP has determined that there are four aspects of returning research results to subjects and releasing the results publicly, with overlap of the concepts along a spectrum:

- Return of incidental findings to subjects

- Return of individual study results to subjects

- Return of general study results to subjects

- Public release of study data

SACHRP has issued four previous recommendations on this matter. SACHRP partially addressed the issue of public release of data in December of 2013 by providing commentary in response to the June 4, 2013, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Request for Comment relating to the availability of masked and de-identified non-summary safety and efficacy data. While this commentary was focused on the issues presented in the FDA request for comment, it also addressed some of the broader issues associated with the public release of study data. On March 25, 2015 SACHRP released a recommendation on the return of general study results to research subjects. SACHRP next released a recommendation on September 28, 2015 on recent changes to HIPAA and CLIA regulations that potentially affect the return of individual research laboratory results. SACHRP then released a recommendation on the return of individual study results to research subjects on May 19, 2016. This final recommendation addresses the return of incidental findings to research subjects. While there is overlap among the concepts, as shown above in the linear Venn diagram, SACHRP believes that each topic is best addressed individually for clarity.

Definition of Incidental Findings

In contrast to the return of general or individual study results to subjects, incidental findings are discoveries of individual-level findings that are unrelated to the goals of the study. Examples include finding an indication of lung cancer in an X-ray done to look for tuberculosis for research exclusion criteria, finding a brain aneurysm during an MRI conducted for brain mapping purposes, or the discovery of a genetic marker unrelated to the goals of the study. While most incidental findings will be discovered during clinical research, be medical in nature and have potential effect on the subject’s health, such as those just mentioned, incidental findings can occur in social behavioral and other fields of research as well, and can have implications that are not directly related to medical care. There will be some findings that could be considered to be both an individual finding and an incidental finding, as noted in the Venn diagram above.

Definition of “Return”

It is also important to define what is meant by “return” of incidental findings. There are several relevant issues. First, there are many ways that results can be returned, such as discussion between the subject and their investigator or healthcare provider, postal mail, or emailing. However, given that incidental findings will often have clinical relevance, their return to the subject should be similar to the return of clinical information in a standard clinical care setting, with the more important and complicated information being delivered personally.

SACRHP considers “return of incidental findings” to subjects to include return of the findings to the subjects directly, to the Legally Authorized Representative (LAR) of adult subjects who lack competence, or to the parents or guardians of pediatric subjects. The incidental findings might also be provided to the subject’s health care provider.

Another issue in considering return of incidental findings is the identity of the individuals who decide whether to return the incidental findings and, if the decision is made to return them, who will do so. The return of incidental findings is generally more a clinical issue than a research issue; therefore the decision whether to return incidental findings could include the subject’s treating physician, the investigator and research staff, the IRB, the hospital ethics committee, or a genetic counselor or other relevant specialist. Because there is great variability in the types of research and research settings where potentially returnable incidental findings might be uncovered, including behavioral research, there is no single preferred model for making decisions about whether to return incidental findings. It is, however, preferable for medical concerns that an individual with a clinical relationship with the subject deliver or be involved with the delivery of information about the incidental finding. This might be the researcher or other research team member who has a clinical relationship with the subject; however, when the researcher is not a clinician or does not have a clinical relationship with the subject, other choices may be more appropriate, such as a genetic counsellor.

For certain types of research, such as genome sequencing, it may be appropriate to return “individual” incidental findings to family members of the proband (i.e., the person serving as the starting point for genetic study of the family) as well as the proband. However, this is a complicated ethical and legal area, and careful consideration should be given to such situations. These considerations will be heavily fact dependent.

Finally, SACHRP notes that as the amount of time grows between the subject’s participation and the identification of the incidental finding, it becomes more administratively difficult to find the subject and to contact the investigator or another appropriate individual to return the finding.

Ethical Foundation

The provision of incidental findings to research subjects is primarily supported by the principle of beneficence. The usual construct of an incidental finding is a directly actionable (clinically or otherwise) finding that needs to be provided to the subject in a timely manner. However, beneficence also provides a directive to avoid harm to subjects, and to the extent that the return of incidental findings to subjects could lead to harm or discomfort, whether physical, psychological, financial, reputational or social, particularly with no offset of direct benefit, there must be consideration of whether it is appropriate to return such findings.

In some studies, it may be impossible to provide incidental findings because the subjects are de-identified or anonymous, for example, certain tissue banking activities, research conducted under a waiver of consent, exempt studies, and cluster randomized studies.

Validity and Actionability of Incidental Findings with Utility

When considering whether or not to return incidental findings that have potential implications for a subject’s physical or mental health, the more likely the findings are to be validated and actionable, the more justification there is for providing them. “Actionable” can be either clinically actionable or personally actionable. At the other end of the spectrum, those findings that are not validated and not actionable carry the least justification for return. One way to visualize this approach is as follows:

| Y/N | Validated | Not Validated |

|---|---|---|

| Actionable | Box 1 - probably indicated | Box 2 - possibly indicated |

| Not Actionable | Box 3 - possibly indicated | Box 4 - probably not indicated |

Box 1 – Individual incidental findings that are validated and actionable.

These would include incidental findings discovered when reviewing results of many standard clinical tests done in the context of research, such as pregnancy tests, liver function tests, EKGs, MRIs, and chest X-rays. There is a strong presumption of disclosure for these incidental findings. From a regulatory perspective, particularly in the medical field, “validated” will usually mean that the test or diagnosis is conducted using devices or assays that have regulatory approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or certification under CLIA from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

Box 2 – Incidental findings that are not validated but could be actionable.

The decision to return incidental findings in this category will be fact dependent. When possible, these non-validated results should be followed up with validated testing to help provide certainty, but in some situations there will not be approved or validated tests available.

Box 3 – Incidental findings that are validated but not actionable.

An example here is a validated genetic diagnosis of Male Pattern Baldness. SACHRP encourages consideration of disclosure in these situations, with consideration given to personal as well as clinical actionability. Again, the decision to return incidental findings in this category is fact-dependent. There is the possibility that the findings in question will become clinically actionable at a later date, either soon or long after the original study has concluded. SACHRP notes that as the amount of time grows between the subject’s participation and the realization that the result is actionable, it becomes more administratively difficult to find the subject and to contact the investigator or another appropriate individual to return the finding.

Box 4 - Results that are neither validated nor clinically actionable.

These can include experimental results in basic science studies, such as a genetic variant that is not known to be associated with the disease of interest or any other disease. There is not a strong presumption to make disclosure the default position for these types of purely experimental results.

When the likelihood of identifying some incidental findings is high in a particular study (for instance, in whole genome sequencing), it may be appropriate to ask the subjects in advance if they wish to receive such information, and considerations around return of particular incidental findings may change if they become actionable in the future.Regulatory Status

HHS and FDA Human Subject Protection Regulations

The HHS and FDA regulations (45 CFR 46 and 21 CFR 50 and 56, respectively) are silent regarding the return of incidental findings to research subjects, and neither directly require nor disallow this activity. However, FDA in ICH E6 Good Clinical Practice has stated that “The investigator/institution should inform a subject when medical care is needed for intercurrent illness(es) of which the investigator becomes aware.” Similarly, FDA in the guidance document “Investigator Responsibilities — Protecting the Rights, Safety, and Welfare of Study Subjects,” says that;

The investigator should also inform a subject when medical care is needed for conditions or illnesses unrelated to the study intervention or the disease or condition under study when such condition or illness is readily apparent or identified through the screening procedures and eligibility criteria for the study. For example, if the investigator determines that the subject has had an exacerbation of an existing condition unrelated to the investigational product or the disease or condition under study, the investigator should inform the subject. The subject should also be advised to seek appropriate care from the physician who was treating the illness prior to the study, if there is one, or assist the subject in obtaining needed medical care.

Note that these guidance documents apply to clinical investigations as defined by the FDA, a distinct type of research.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA)

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) (45 CFR 164) requires, among other things, that patients have access to their Protected Health Information (PHI) upon request. There are certain exceptions, including some for research. Subjects in research studies can obtain incidental findings from the research if they are part of the subjects’ “designated record set,” but those results may be withheld while the research is being conducted in order to protect the blinding and other research activities performed to reduce bias in the conduct of the research, as long as subjects have been informed of the access restrictions in place during the trial. However, concerns for issues such as unblinding are less likely to arise with return of incidental findings, and this should be factored into any decision of whether to return incidental findings.

In responding to a request for access, a covered entity is not required to create new information, such as explanatory materials or analyses, that does not already exist in the designated record set. However, individuals have a right under HIPAA to access PHI about themselves in human readable form. Regardless of whether there are plans to return incidental findings, there may be an independent legal right under HIPAA for research participants upon request to have access to results in their designated record set. There are laws to consider in determining whether research information can or must be provided to subjects.

More information on this issue is available at http://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/guidance/access/index.html.

The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA)

The Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) (42 CFR 493) is intended to ensure that laboratory results used in patient care are accurate. CLIA contains an exception for research laboratories to return certain research results at 42 CFR 493.3(b)(2), by stating that the rules do not apply to “Research laboratories that test human specimens but do not report patient specific results for the diagnosis, prevention or treatment of any disease or impairment of, or the assessment of the health of individual patients.” However, if individually identifiable research results are reported from the laboratory to another entity and the results are available to be used for clinical care for individual patients, then this exception does not apply.

SACHRP has separately issued a recommendation regarding HIPAA and CLIA and the return of individual results from research laboratories, and the inconsistency in the content and application of those regulations. These considerations may arise with respect to return of incidental findings as well. See the SACHRP recommendation issued on September 28, 2015.

Administrative Considerations

Inclusion of Plans for Incidental Findings in the Protocol and Consent Form

Due to the definition and nature of incidental findings, it will not be common to include plans in research protocols for their return. Likewise, it will not be common to address their return in consent forms. However, there may be certain research protocols that involve processes such that the likelihood of identifying incidental findings justifies their discussion in the protocol and consent form. Examples might include protocols involving imaging, genetic testing, or testing for infectious diseases.

Standard Process for Incidental Findings across Protocols

Some institutions, IRBs, and sponsors may find it useful to have standard procedures for incidental findings that can be applied across protocols. Such procedures may consider the potential for disagreement about what is “actionable” and identify suggestions for determinations of actionability, especially when confirmatory testing or clinical input is needed. Because the likelihood of identifying potentially actionable incidental findings varies across studies, such procedures should be designed to be applied flexibly to different circumstances. They need not --but may -- involve the IRB, as incidental findings generally are clinical issues rather than research issues. As noted on a protocol level basis, a standard process may make more sense in institutional settings where incidental findings are likely, such as imaging, genetic testing, or testing for infectious disease, when conducted for research purposes. For most research, it may be more than sufficient for the IRB to ask investigators to consider whether any potentially actionable incidental findings might arise and how the investigators would proceed if such a finding were identified, and to be available for consultation if questions arise.

Single IRBs

Single IRBs for multi-site research are becoming more common, a trend which will continue under the NIH policy and the Final Rule. For a single IRB, the return of incidental findings can be considered on a protocol-specific basis, or can be considered as an issue of local research context. As noted above, institutions might have standard processes for handling incidental findings.

The Final Rule and Provisions Regarding Return of Results

The Final Rule has new provisions regarding return of results at .104(d)(8), .116(b)(8), and .116(d)(6). For each of these provisions it is uncertain whether either protocol specific or standard processes for providing incidental findings might constitute a plan to return individual research results within the meaning of these sections. One clue is that the preamble cites the SACHRP recommendation on return of individual research results.

.104(d)(8) states:

(8) Secondary research for which broad consent is required: Research involving the use of identifiable private information or identifiable biospecimens for secondary research use, if the following criteria are met:

(iii) An IRB conducts a limited IRB review and makes the determination required by §_.111(a)(7) and makes the determination that the research to be conducted is within the scope of the broad consent referenced in paragraph (d)(8)(i) of this section; and (iv) The investigator does not include returning individual research results to subjects as part of the study plan. This provision does not prevent an investigator from abiding by any legal requirements to return individual research results.

.116(b)(8) states:

(8) A statement regarding whether clinically relevant research results, including individual research results, will be disclosed to subjects,

.116(d)(6) states:

(6) Unless it is known that clinically relevant research results, including individual research results, will be disclosed to the subject in all circumstances, a statement that such results may not be disclosed to the subject;

Conclusion

Because incidental findings are more a clinical than a research issue, SACHRP recommends that the agencies specifically acknowledge that incidental findings are not individual research results. This will ensure flexibility in the consideration of whether and how to return incidental findings, and will make clear that IRBs and institutions are not out of compliance if they do not address returning incidental findings. The Final Rule’s provisions about return of individual research results assume a structured and organized approach to return of individual research results that does not apply to incidental findings. It may be administratively efficient, and helpful to some principal investigators, to include IRBs and research offices in the decision of whether or not and if so, how to return incidental findings, but it is not required.