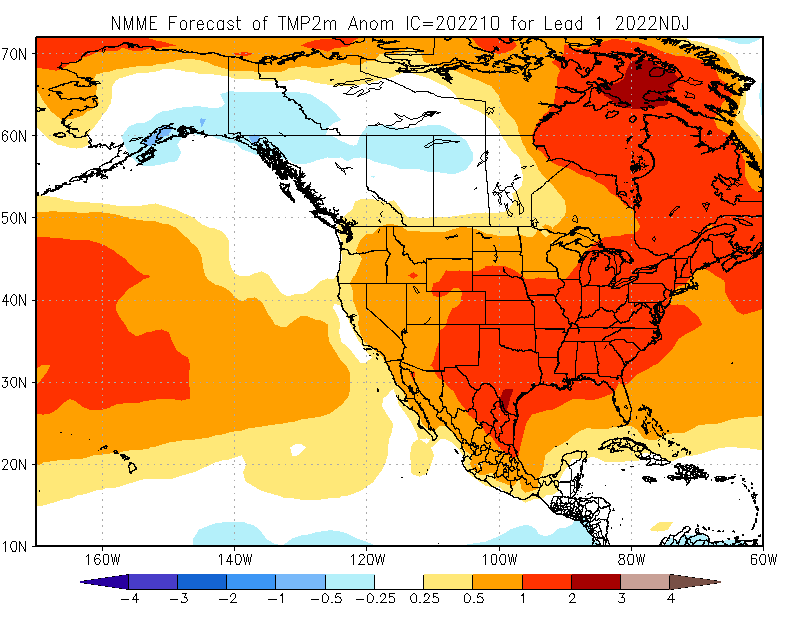

Image source: https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/NMME/current/images/NMME_ensemble_tmp2m_us_season1.png

Figure: The North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME) predicts that average temperature over the next 3 months (September – November) will be 1.8–3.6°F (1–2°C) hotter than average across parts of the contiguous U.S. For more information about this model or prediction, please refer to the NMME website.

For November – January, the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME) predicts that the average temperature will be 0.9 – 3.6°F (.5 – 2°C) above-normal for most of the continental United States. However, parts of Alaska will experience temperatures 0.45 – 1.8°F (0.25 - 1°C) cooler than average. The NMME integrates multiple forecasts of the next 90 days to build the best estimate of temperatures and precipitation over that time frame. Note that although many regions may expect a warmer 90-day average temperature, this is not the same as your local weather forecast, in which large fluctuations in temperature may be predicted from day to day.

Health Impacts During the Heat Dome of 2021

During June–July 2021, the western U.S. experienced a record-breaking heat wave that lasted for several days. Estimated heat-related deaths and illnesses demonstrate the tragic toll of the heat wave on public health. Comparing the health records from June 26–July 10 between 2021 and 2020, heat-related deaths increased from 2 to 145 in Washington, 0 to 119 in Oregon, and 12 to 25 in California. These estimates were provided by the California Department of Public Health, Oregon Health Authority, and Washington State Department of Health. For context, the CDC estimates an average of 702 heat-related deaths per year for the entire U.S. (based on 2004–2018 data).

Heat Affects Health in Many Ways

Warmer temperatures increase the risk for a diverse range of health risks. For example:

- An increased risk of hospitalization for heart disease.

- Heat exhaustion, which can lead to heat stroke if not treated, can cause critical illness, brain injury,

and even death. - Worsening asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as heat increases the production of ground-level ozone.

- Dehydration, which can lead to kidney injury and blood pressure problems. Some kidney damage can become irreversible with repeated or untreated injury.

- Violence, crime, and suicide may increase with temperature, adding to the rates of depression and anxiety already associated with climate change

- Some medications increase the risk of heat-related illness. These include diuretic medicines (sometimes called “water pills”), antihistamine medicines (including many allergy medicines), and many antipsychotic medicines used to treat a variety of psychiatric and neurologic illnesses. Please review this list of common psychiatric medications that can impair the body’s normal ability to cool itself.

Spotlight on Health Equity: Health Impacts in Rural Areas

![Emergency Department Visits with a Diagnosis Directly Indicating Heat Exposure per 100,000 Population, 2016-2019. Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), State Emergency Department Databases (SEDD) and State Inpatient Databases (SID), 2016-2019.]](https://public3.pagefreezer.com:443/content/HHS.gov/27-12-2022T06:17/https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/nonsupp-heat-stcofips-2016-2019-alled.png)

In April 2022, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality used the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) 2016–2019 to estimate county-level population rates of emergency department (ED) visits with a diagnosis directly indicating heat exposure. The analysis was limited to records of ED visits, regardless of hospital admission, at community hospitals, excluding rehabilitation and long-term acute care facilities, with any-listed diagnosis directly indicating heat exposure. This analysis includes ED data from 2,550 counties in 39 States and the District of Columbia, representing 85 percent of the population and 81 percent of all counties in the United States in 2019. Among the 1,122 rural counties, 152 (13.5%) had heat-related ED visit population rates of 85 or more per 100,000 population (i.e., 90th percentile of population rates). In contrast, among the 344 large metropolitan counties, 8 (2.3%) had heat-related ED visit population rates in the 90th percentile. The report highlights that a larger proportion of rural than large metropolitan counties experience a high rate of heat-related illness, although there are more heat-related ED visits in large metropolitan areas (n=135,585 ED visits) than in rural areas (n=30,115 ED visits).

Resources for People at High Risk of Heat-Related Health Problems

Certain populations with limited resources may have restricted access to information on heat illness prevention, cool indoor environments, and government programs that provide critical support. Find more resources on heat illness prevention from Heat.gov and CDC websites.

Worker Health

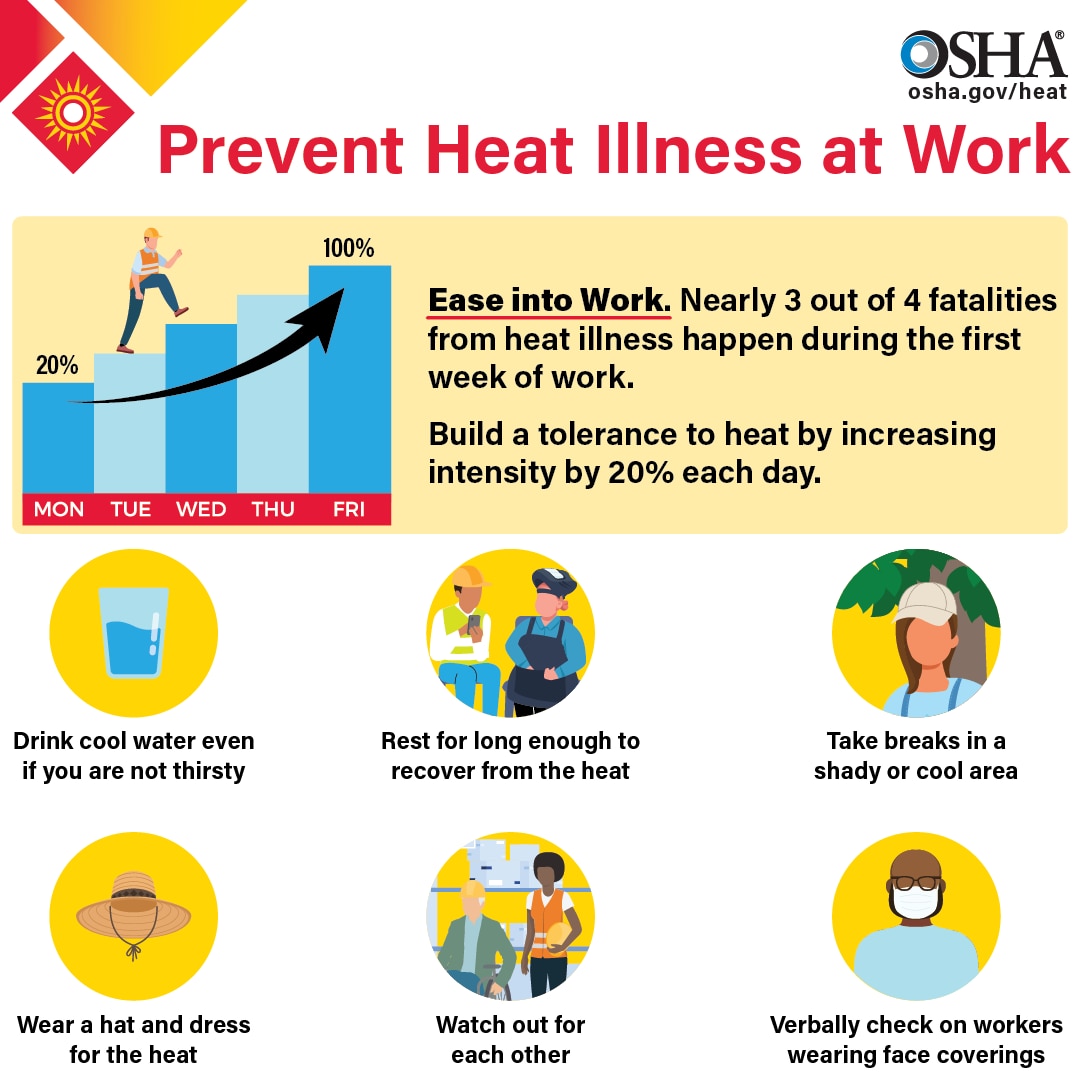

Occupations that require strenuous work outdoors pose a high risk for heat-related illness. This includes construction workers, farmers, agricultural workers, delivery workers, athletes, landscapers, and others. Learn more about the dangers of working in heat. Employer responsibilities and resources for safety are also available through the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Heat Illness Prevention campaign.

- The Heat Safety Tool provides real-time heat index and hourly forecasts, specific to your location, as well as occupational safety and health recommendations from OSHA and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Worker Training Program has heat safety and health training for at-risk workers.

- The Health Resource Services Administration (HRSA) funds National Training and Technical Assistance Partners — Farmworker Justice and Migrant Clinicians Network that helps clinicians prevent and treat heat-related illness among agricultural workers.

Image source: https://www.osha.gov/heat

Staying Safe Indoors

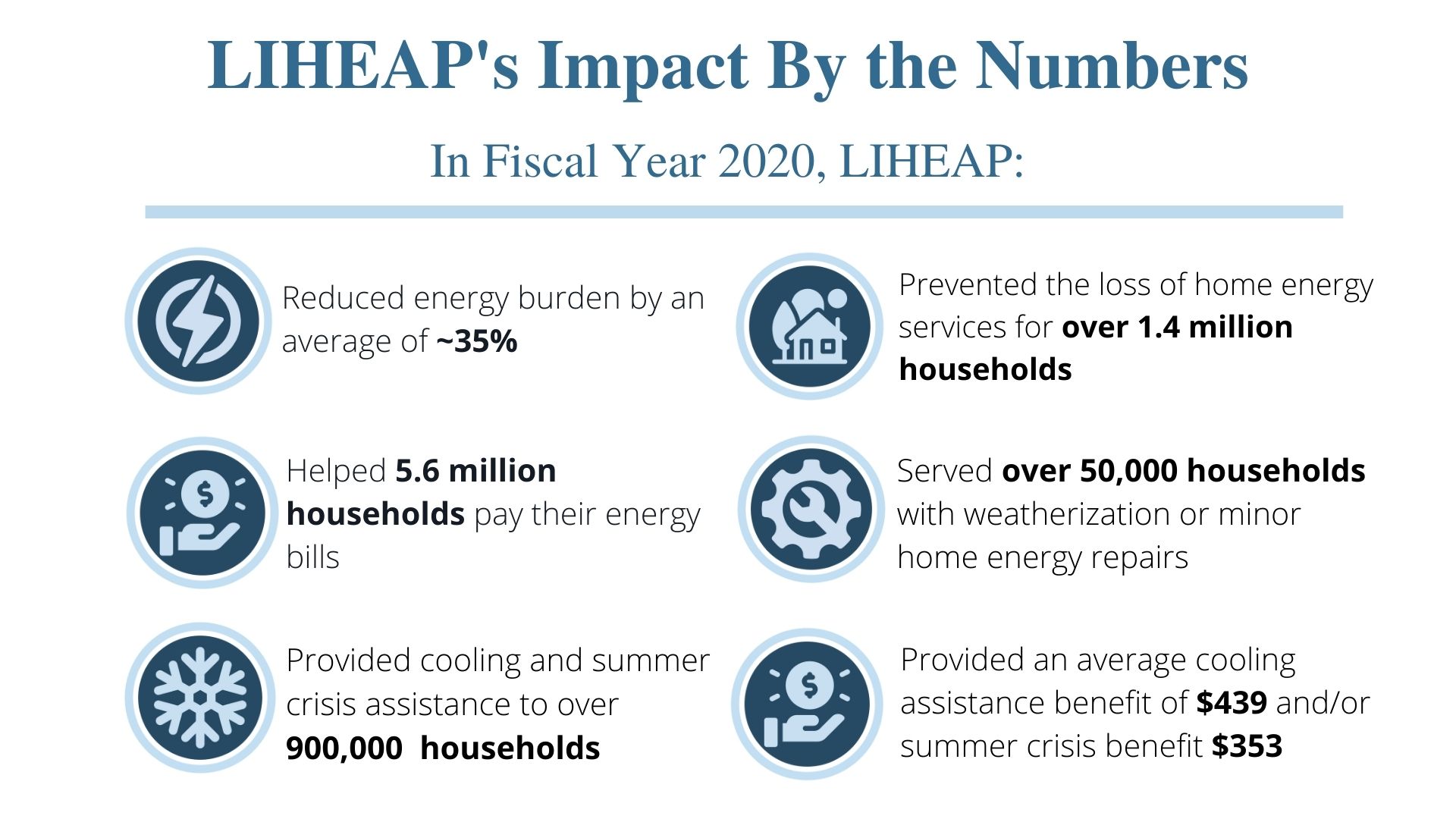

- The Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) and the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) help keep families safe and healthy through initiatives that assist families with energy costs. To inquire about LIHEAP assistance, call the National Energy Assistance Referral (NEAR) hotline at

1-866-674-6327. - HHS has issued guidance that for the first time expands how LIHEAP can promote the delivery of efficient air conditioning equipment, community cooling centers, and more.

- The National Institute on Aging resource Hot Weather Safety for Older Adults offers background information on heat stroke, who is at risk, lowering your risk, and best practices.

- Medicare Advantage (MA) plans may provide Special Supplemental Benefits for the Chronically Ill (SSBCI) with equipment and services that improve indoor air temperatures and quality (such as portable air conditioners) to chronically ill patients.

Image sources: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/ocs/COMM_LIHEAP_Earth%20Day_FY2022.pdf, https://liheappm.acf.hhs.gov/datawarehouse

Best Practices for Emergency Managers

This CDC report on Heat Response Plans reviews steps emergency managers and health officials can take to develop and implement measures to protect their communities. Spikes in energy demand should be expected during summer months as air conditioning use increases. The combination of sagging power lines (copper expands as it heats up, thus increasing impedance and reducing throughput) and increased energy demands can cause power failures that make certain populations more vulnerable when the risk is highest. The HHS emPOWER pcollects and shares de-identified Medicare data to help response agencies take action to protect the health of Medicare beneficiaries who depend on vulnerable electrical medical equipment.

Real-time information on health impacts from extreme heat can also help decision-makers implement strategies to reduce risk. CDC’s Heat and Health Tracker provides regular updates on the rate of heat-related Emergency Department visits (organized by HHS regions) and observed temperature.

If you are a local organization planning to open a cooling shelter, consider referring to CDC guidance on how to maintain a safe shelter during a heat wave.

Check out SAMHSA’s newly launched Climate Change and Health Equity site for more information on the behavioral health impacts of climate change, preparing for a disaster, and resources for disaster planning and climate change education.

Clinical Best Practices

A heat stroke is a medical emergency, and rapid recognition and aggressive early treatment are essential to reduce morbidity and mortality (as illustrated below).

See https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33856299/ for the full algorithm.