Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections

March, 2022

Question posed to the SACHRP SAS Subcommittee:

To what extent should IRBs identify and consider risks to non-subjects during the process of review and approval of research involving human subjects?

Summary Statement

Federal regulations govern the conduct of research and define a framework for the protection of human research subjects from research-related harm. Examples of exposure of individuals other than research subjects to the risks of research are well-known, and these risks may be significant. Research may introduce risk to bystanders, to communities in which individual subjects and non-subjects reside, to research team members, and to other personnel at research sites. Harm may arise from research interventions, procedures, and environmental manipulations, as well as from the findings, outcomes, or conclusions of research. Subpart A alludes to non-subjects in the requirement for the reporting of "unanticipated problems involving risks to subjects or others," and Subpart B requires IRB consideration of risks to fetuses or neonates in research involving pregnant individuals, but otherwise does not explicitly address harm to non-subjects or describe the scope of IRB responsibility in the review and mitigation of these risks. Despite the lack of a clear regulatory mandate, IRBs regularly consider risks to non-subjects as falling within their ethical remit. SACHRP therefore asserts that institutions and investigators have an obligation to consider risks to non-subjects as part of the broad ethical responsibilities of the conduct of human research; this obligation is currently recognized by IRBs and falls within their purview and expertise.

Conclusions:

- Examples of exposure of individuals other than research subjects to the risks of research are well-known and these risks may be significant. Research may also introduce risk to communities in which individual subjects and non-subjects reside, to research team members, and to other personnel at research sites.

- For the purpose of this document, "non-subjects" are living individuals who are, or who are likely to be, exposed to research risk and who do not meet the regulatory definition of human subject. When a research intervention or interaction occurs with such individuals, or when identifiable private information is collected from living individuals solely to evaluate their exposure to risk, this activity does not, in general, constitute research under the HHS definition; it is not a systematic investigation aimed at creating generalizable knowledge. Such individuals are therefore also not research subjects. In relation to FDA rules, non-subjects are individuals who are not recipients of a test article or are not controls as part of an experiment.

- Subpart A requires the reporting of "unanticipated problems involving risks to subjects or others," and Subpart B requires IRB consideration of risks to fetuses or neonates (who may not be subjects). While HHS and FDA regulation do not otherwise explicitly address harm to non-subjects or describe the scope of IRB responsibility in the review and mitigation of these risks, IRBs commonly consider research risk as it impacts non-subjects and their communities as a logical extension of their oversight responsibilities.

- The Belmont Report supports the position that IRBs and investigators each have an obligation to identify and consider risks to non-subjects. Other international codes of research ethics (Declaration of Helsinki, CIOMS, TCPS among others) directly and indirectly reference duties to non-subjects, both individuals and their communities.

- The U.S. government’s provision of reparations to the infected partners and offspring of the subjects of the PHS syphilis studies at Tuskegee and the U.S. led syphilis experiments in Guatemala provide examples of formal recognition that the ethical responsibilities of research extend beyond those owed to research subjects alone.

- Acknowledgement of the legitimate concerns about IRB over-reach, "mission creep," or burden does not, in and of itself, preclude meaningful ethics review of risks to non-subjects or justify inattention to them.

- IRBs bring unique expertise to the consideration of the harms associated with research that may affect individuals who are not human subjects, and this function falls reasonably within its purview and expertise.

SACHRP Recommendations

- During the process of IRB review and approval, IRBs should identify and seek to minimize risks to living individuals who are, or who are likely to be, exposed to research-related risk, even when they do not meet HHS or FDA definitions of human subject.

- Although all research stakeholders are responsible for recognizing and addressing risks to non-subjects, and many IRBs regularly consider such risks, SACHRP takes the position that the IRBs should assume responsibility for protecting non-subjects who may be unknowingly exposed to risk and who cannot take self-protective measures or who may be exposed to experiential harms (e.g. the sexual partner of subject testing an investigational barrier contraceptive, stigma associated with the research results, etc.). This responsibility, however, should be limited in scope. In addition, where separate institutional oversight bodies provide expertise and authority in the assessment and management of risk to non-subjects, IRBs should be permitted to fulfill this obligation by relying on those reviews or seeking consultation when required or appropriate.

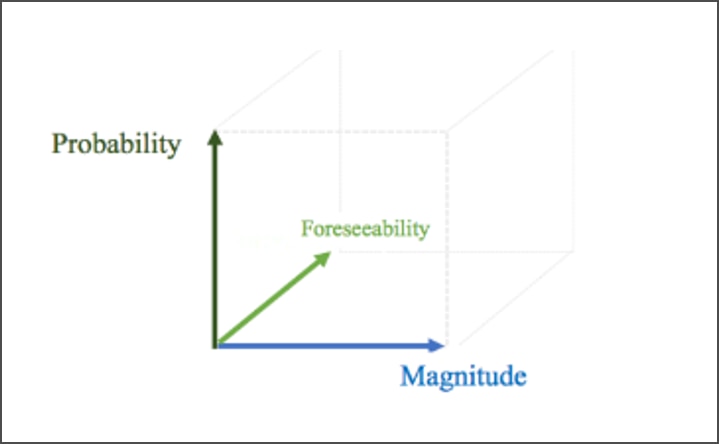

- Characterization of risk to non-subjects along the dimensions of probability, magnitude, foreseeability, and causal proximity during review may help establish thresholds for IRB decision-making.

- IRBs should not routinely consider research related harms that are no more likely or serious than those that represent the ordinary risks of daily life. SACHRP recommends that IRBs conduct review of non-subject risk only when those risks are greater than minimal risk.

- Regardless of the type of risk to the research team or other personnel, SACHRP recommends that IRBs be cognizant of risks to personnel and consider engaging the appropriate authorities within the institution to review and manage such risks.

- The IRB’s assessment and management of risk to non-subjects requires a careful delineation of responsibilities in order to minimize a duplicative, unnecessary, or inexpert review better conducted by other institutional entities or in consultation with other entities.

- IRBs may consider mechanisms to inform non-subjects of potential harms related to research, may determine that low risk "exposures" do not require disclosure, or may decide that disclosure may be impracticable or itself introduce harm to the subject.

- SACHRP recommends that IRBs consider the need to formalize in policy the review of risk to non-subjects and the referral to or coordination of review with other expert external or institutional bodies and functions.

- Whether the pregnant partners of participants in investigational treatment studies are research subjects has been the subject of controversy in part reflecting the disharmony in HHS and FDA definitions of research subject. SACHRP does not consider the collection of safety data from a person who becomes pregnant during the partner’s research participation, in and of itself, to constitute human subject research, and therefore that pregnant individual does not fulfill the definition of human subject under HHS or FDA rules.

Introduction

Subpart A of the U.S. federal regulations governing the conduct of human subject research requires the reporting of unanticipated problems "involving risks to subjects or others." In Subpart B, IRBs are required to consider risks to pregnant women, fetuses, and neonates. These examples reflect a recognition in the language of the regulations that research can expose individuals other than research subjects to research-related harms, and further, define related responsibilities for IRBs. However, the regulations appear otherwise silent regarding anticipated risks to non-subjects, raising the question of the extent to which IRBs may, or should, identify and consider risks to non-subjects during the process of review and approval of human subject research. Given what would otherwise seem to be a logical ethical responsibility of the oversight of human subjects research, this question merits analysis.

Apart from the review of unanticipated problems and Subpart B requirements referenced above, the federal regulations do not speak to matters of research harm in relation to individuals who do not meet the regulatory definition of research subject. But examples of exposure of individuals other than research subjects to the risks of research are well-known. Research may also introduce risk to communities in which individual subjects and non-subjects reside, to research team members, and to other personnel at research sites.

As the criteria for approval of research at 45 CFR 45.111 and 21 CFR 56.111 are silent regarding risks to non-subjects, some have argued that the IRB is not required to evaluate risks to such non-subjects during the process of protocol review and approval. Further, while IRBs may bring unique expertise to the process of identifying and evaluating risk, other parties, for example, institutional infection control and occupational safety functions, or other review bodies, routinely play a role in the assessment and management of specific categories of risk to non-subjects. While IRBs may rely on such reviews or seek consultation when required, concerns with duplicate review or an expanded scope of IRB responsibility ("mission creep") are regularly cited regarding IRB review of risks to non-subjects.

Many IRBs are cognizant of an obligation to non-subjects and address risk to non-subjects as a matter of routine. The Belmont Report, discussed further below, supports the position that IRBs and investigators each have an obligation to identify and consider risks to non-subjects. This SACHRP guidance also supports that view, addresses contrary perspectives, defines and limits "non-subjects" for this purpose, and provides an ethical argument and practical recommendations regarding the IRB’s role for its application.

Definition of "Non-Subjects Exposed to Research Risk"

These recommendations focus on non-subjects exposed to research risk; this includes:

- Living individuals who are, or who are likely to be, exposed to research-related risk, but who do not meet the regulatory definition of a human subject; and

- Living individuals exposed to research risk about whom investigators collect identifiable private information or with whom interactions/interventions occur solely for the purpose of evaluating their exposure to research risk.

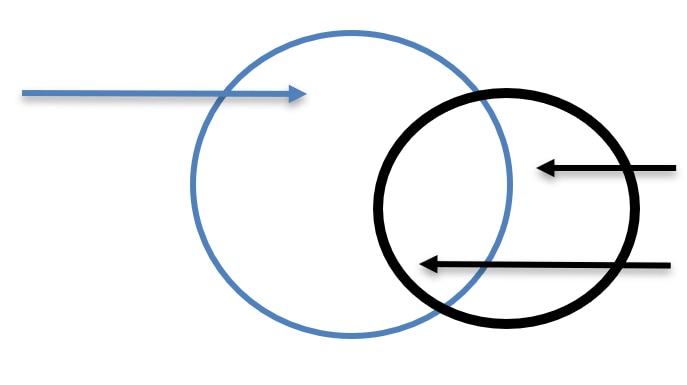

These recommendations distinguish the second category of individuals from human subjects who are the main scientific focus of the research because in this case, data is collected about them, or interventions occur with them only to assess their exposure to risk (Figure 1) not to create generalizable knowledge. For simplicity’s sake, we refer to both categories as "non-subjects" in this document.

Figure 1. Individuals Exposed to Research Risk

|

Human Subject: |

Image

|

Non-Subject: |

As defined herein, non-subjects who are, or who are likely to be, exposed to research risk are not voluntary research participants, are not recruited to participate in research, and do not participate in consent discussions or provide prospective consent. Other commonly used terms (bystanders, incidental subjects, third parties, etc.) capture different but overlapping subsets of non-subjects. For example, the term "bystander" ordinarily implies a physical presence, and some of the risks of the sort we contemplate routinely occur at a distance. Similarly, "incidental" or "third party" may imply something that is of lesser importance (of a chance or minor consequence). Therefore, we have decided not to use these terms.

Individuals who are not subjects can be exposed to research risk singly or along with members of the groups or communities to which they belong. They may have a relationship to a research participant (a co-worker, a sexual partner, a family member), or have none. The nature of such risks may be physical, emotional, or be of interpersonal, social, or cultural relevance, for example, by causing reputational harm or contributing to stigma or burden in a community. Non-subjects may be exposed to risk in any type of research, including biomedical, social, behavioral, and educational.

For the purpose of this document, it is also useful to subdivide risk to non-subjects into 1) those harms (and potential harms) introduced by research interventions, manipulations, and procedures that could affect non-subjects who come into contact or proximity with subjects or interventions and 2) harms to the community from which subjects are drawn that result from the design, conduct, findings, outcomes, or conclusions of the research, or the approach to dissemination of study results.

Finally, the current research environment involves activities that collect, use, store, and share data derived from individuals that are not individually identifiable. Such research does not constitute human subjects research or fall within categories of research that are exempt or otherwise not subject to regulatory oversight or IRB review. Nonetheless, the published findings and conclusions of such work may introduce group or community harm. SACHRP acknowledges this limitation in regulatory and procedural coverage, and asserts that the identification and mitigation of such harm is the individual and collective responsibility of the many stakeholders in the research enterprise, including sponsors, institutions, investigators, and journal editors, among others.

See, Table 1 for specific examples.

Examples of non-subjects exposed to research risk

In this document, we discuss the broad set of non-subjects who may be exposed to research risk. Non-subjects potentially exposed to risk include family members of subjects, sexual partners, researchers and other study team members, and other personnel that interact with research subjects (such as visiting nurses or other providers, personnel at research facilities, etc.).

The IRB review of recent research on the infectious agent SARS-CoV-2 underscores the limitations of existing regulation and guidance with regard to non-subjects exposed to potentially lethal risk by virtue of physical proximity to a research subject. Other examples are noted below.

When audio-visual or electronic data is gathered in public spaces using wearable sensors or other recording technology, identifiable data from non-subjects may be incidentally or inadvertently captured and obtained by investigators. Although some of this information may be considered publicly available, if they were aware, non-subjects may object to having audio and video of themselves captured. Nevertheless, risk exists and require mitigation when it is possible that the recorded information could place the non-subjects at risk of criminal or civil liability or otherwise be damaging to their financial standing, employability, educational advancement, or reputation.

In other circumstances, non-subjects are at risk as a result of direct physical or sexual contact. In this manner, sexual partners, breast-feeding infants, and fetuses, among others, can be non-subjects exposed to research risk, often in the context of investigational therapies and interventions. Research involving alteration in the human genome may cause heritable effects with downstream consequences for offspring. Subjects in HIV prevention or HIV cure research may engage in high-risk sexual behavior, when as has been observed, they overestimate or misunderstand the protective effects of the research intervention. As a result, their sexual partners may be exposed to a greater risk of infection as a result of the subject’s high-risk behaviors. In this scenario, the IRB may consider these risks and determine that the research informed consent process and protocol-required counseling of subjects about risk-taking behaviors sufficiently mitigates risk to non-subjects or that these messages should be enhanced. Caregivers of subjects in studies of the management of delirium in dementia patients, for example, may be exposed to harms when ineffective therapy or delay to effective treatment gives rise to aggressive behavior (in some studies in which research data is systematically collected from caregivers of individuals with dementia, the caregiver would be subjects). When biological or genomic research provides information about predisposition to illness, ancestry, paternity, or kinship, data on non-subjects may be incidentally obtained, conveyed, stored, and used exposing non-subjects to harm related to the receipt of unwanted information or loss of privacy.

Finally, cluster randomized trials (CRT) take many forms and involve complex considerations in the application of the regulatory definition of subject. A CRT may introduce risks to both those from whom data is collected and others exposed to the research intervention or environmental manipulation but from whom no data is collected. In its Recommendations on Regulatory Issues Involving Cluster Randomized Trials (2016), SACHRP recommended that both of these categories of individuals be considered human research subjects and afforded appropriate research protections. When an IRB determines that an individual exposed to a research intervention is not a research subject under the HHS rules, risks to such individuals (as non-subjects) should be identified and considered. The guidance outlines procedures for determining when an activity constitutes research and when human research subjects are involved, and we refer the reader to this document for detailed consideration of CRTs.

Table 1 includes additional examples provided as prototypes to assist IRBs in recognizing some ways in which study questions, procedures, and reporting give rise to harms to non-subjects. While most of the examples are derived from actual (and referenced) studies, these brief descriptions may describe only a single aspect of the study to illustrate that actual harm occurred to non-subjects. The examples are grouped according to whether the risks of harm posed to non-subjects are physical only; also include non-physical, or social risks such as stigmatization or discrimination; or are exclusively non-physical. In general, studies outcomes that pose social and reputational risks to subjects may also add stigma or burden to non-subjects (families, communities) of subjects. IRBs should seek to identify and mitigate such harms.

|

Example |

Nature of the Potential Harm |

Type of Risk |

|---|---|---|

|

May expose a sexual partner, pregnant partner (and fetus/newborn), family member, social group, community, or other individuals who are in close proximity to the subject to a biological agent that poses a health hazard; depending on the efficacy of the investigational vaccine, there may be an increased risk of virus transmission. |

Physical |

|

|

May expose a sexual partner or pregnant partner (and fetus/newborn) of the subject to HIV, depending on the efficacy of the therapy. |

Physical |

|

May expose visitors or neighbors to risk when visiting residents living in units with the specialized plumbing utilizing recycled wastewater when the safety of the recycled wastewater is unknown. |

Physical |

|

Under certain circumstances, may increase risk to pregnant partners, infants, or others who come into close contact with the subject or affect a women’s ability to become pregnant if she or her partner are exposed. Risks to research staff involved in the use of ionizing radiation are well documented—for example, the increased risk of cataracts in interventional cardiologists. |

Physical |

|

If viral shedding occurs, there is potential for transmission to non-subjects such as the subject’s family members, healthcare workers, research team members, or other individuals who come in close contact with the subject. |

Physical; Non-Physical (stigma, loss of privacy, etc.) |

|

|

May expose a subject’s family members and others living in the home or nearby, including pregnant women and their fetus/newborn, to toxic pesticides that could pose a health hazard; could introduce non-physical harms because of a loss of privacy or legal risk due to observed unlawful behavior during home visits ( e.g., evidence of unsafe conditions, or evidence of abuse or neglect in the home). |

Physical; Non-Physical (loss of privacy, legal risk, etc.) |

|

May expose a subject’s family members and others living in the home to infection; could be harm associated with loss of privacy (the mere fact that health workers are known to be visiting the home) or legal risk due to observed unlawful behavior, unsafe conditions, or evidence of abuse or neglect in the home. |

Physical; Non-Physical (stigma, loss of privacy, legal risk, etc.) |

|

May expose the subject’s family members, others living in the home, or individuals outside of the home to physical risks; changes in behavior could have an emotional impact on individuals who interact with the subject. |

Physical; Non-Physical (psychological, etc.) |

|

Stakeholder communities or "indirect participants" such as health care providers, hospital staff, patient families, and non-trial participant patients in need of service that may be affected by exposure to the intervention under study or by the outcome of the research (as non-subjects) in the clinical setting where the PCT is occurring. |

Physical; Non-Physical (lack of autonomy, etc.) |

|

Family members of subjects with this genetic variant, who have not given consent, may be burdened with this information, related psychological harm, and a risk of discrimination in eligibility to life or long-term care insurance. |

Non-Physical (psychological, discrimination, etc.) |

|

|

May cause reputational harm to an entire household if a neighbor learns that the study is only including people with certain risk factors or behaviors. Household members may be identified merely because their household is participating in the study involving sexually transmitted diseases. |

Non-Physical (loss of privacy, stigma, etc.) |

|

Individuals may be exposed to psychological harm, potential stigmatization, or discrimination when research links genetic characteristics with impulsivity in an identified group. The failure to consult the community prior to dissemination of results could lead to further harms and distrust of the research process. |

Non-physical (community stigma, psychological, distrust, etc.) |

|

Individuals/groups may be exposed to psychological and reputational harm or stigmatization based on the association of alcohol use with the identified group or community. The failure to consult the community prior to dissemination of results could lead to further distrust of the research process. |

Non-physical (community stigma, psychological, distrust, etc.) |

|

The research may stigmatize family members of adolescents with a juvenile record and perpetuates stereotypes regarding the racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic status of the study population. The research could be perceived as linking study population characteristics (such as race/ethnicity) to the biology of violence which could further perpetuate discrimination. |

Non-Physical (stigma, discrimination, distrust, etc.) |

|

The research may stigmatize less affluent or disadvantaged residents by virtue of the apparent association between credit scores and academic and professional performance. The research could worsen elitism in medicine and discrimination against low-income residency applicants. |

Non-Physical (stigma; discrimination) |

Regulatory Parameters

The Basic HHS Policy for Protection of Human Research Subjects and Subpart B explicitly concern themselves with risk to individuals other than subjects at 45 CFR 46.108(a)(4) in the context of a requirement for IRBs to:

"(4) Establish and follow written procedures for ensuring prompt reporting to the IRB; appropriate institutional officials; the department or agency head; and the Office for Human Research Protections, HHS, or any successor office, or the equivalent office within the appropriate Federal department or agency of (i) Any unanticipated problems involving risks to subjects or others or any serious or continuing noncompliance with this policy or the requirements or determinations of the IRB..."

While this passage does not state that IRBs have a duty to minimize risks to "others," it acknowledges the potential for harm to non-subjects as a matter of relevance to the work of IRBs.

In addition, Subpart B, Additional Protections for Pregnant Women, Human Fetuses and Neonates Involved in Research, defines duties of IRBs in connection with evaluating risk to the fetus (as non-subjects) in research involving pregnant individuals at 45 CFR 46.204. A pregnant person may not participate in research that involves more than minimal risk if there is no prospect of direct benefit to [that person or] the fetus. For example, at 45 CFR 46.204(b) states:

"The risk to the fetus is caused solely by interventions or procedures that hold out the prospect of direct benefit for the woman or [our emphasis] the fetus; or, if there is no such prospect of benefit, the risk to the fetus is not greater than minimal and the purpose of the research is the development of important biomedical knowledge which cannot be obtained by any other means; ..."

Apart from the reference to an obligation by the IRB to evaluate risk to "others" in Subpart A, and to the fetus in Subpart B, HHS regulations governing the review and conduct of human subject research, including the criteria for approval of research at 45 CFR 46.111, make reference only to risk involving "subjects." While the term "subject" is widely understood to mean "human research subject" as defined at 45 CFR 102(e)(1), there are compelling reasons to broaden the application of protections to others who are subject to research risk. Further, the regulations include no specific language prohibiting IRB review of research risk involving non-subjects.

Finally, 45 CFR 46.111(2) reads, "The IRB should not consider possible long-range effects of applying knowledge gained in the research (e.g., the possible effects of the research on public policy) as among those research risks that fall within the purview of its responsibility." This exclusion from IRB consideration of risks related to the "long-range effects" of the application "of knowledge gained" provides a useful boundary for IRB review of risks to non-subjects. In contrast to the 45 CFR 46.111(2) preclusion, identifying the risks of research to non-subjects should focus on direct and immediate effects on individuals or communities arising from the design and conduct of the research or the dissemination of research results (e.g., loss of privacy, stigmatization, legal risk).

Ethical Considerations for the Assessment of Risk to Non-subjects

The need for oversight of human research and protection of subjects involved in research is well understood, having emerged in the aftermath of a long record of human research abuses and experimentation conducted in secret.17 But recognition of the fact that research can harm non-subjects is not new. Beginning in 1975, for example, the United States government made reparations to twenty-two wives, seventeen children and two grandchildren who likely contracted syphilis from the men studied as subjects by the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) Syphilis Study at Tuskegee.18 19 Reparations are also being sought from the victims of the Guatemalan Sexually Transmitted Disease Experiments in which research subjects and their families and descendants continue to suffer from untreated STDs as a result of the study.20

The Belmont Report makes mention of the fact that "Risks and benefits of research may affect the individual subjects, the families of the individual subjects, and society at large (or special groups of subjects in society)" while asserting that "In balancing these different elements, the risks and benefits affecting the immediate research subject will normally carry special weight." Belmont’s consideration of risks to non-subjects (the families of the individual subjects), in the relation to "Beneficence," is perhaps a reference to this harm done to the families of the USPHS study subjects. It defines an ethical obligation, albeit one not explicitly required by the language of the regulations.

Other ethical guidelines such as the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki, and the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) Guidelines also reference non-subjects. The Declaration of Helsinki, emphasizes the rights and interests of individual research subjects, but a broader duty to others affected by research risk for physician investigators is required by Principle 11, "[m]edical research should be conducted in a manner that minimizes possible harm to the environment" and the CIOMS Guidelines, acknowledges risk to non-subjects in the context of community impact (not just to individual subjects). As noted by one author, CIOMS "acknowledge some risks to bystanders, namely, that research may affect normal care in a community and that publication of study results may stigmatize and otherwise upset certain groups, but they recommend mere "sensitivity" to these risks. ..."21

Other ethical guidelines and policy statements acknowledge the obligation of both the researcher and ethics committee to consider the risk to subjects and non-subjects. For example, the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS2 2018) (a joint policy published by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council) acknowledges that "risk may involve harm to participants or others" (for example, "[r]esearch in certain disciplines, such as epidemiology, genetics, sociology or cultural anthropology, may present risks that go beyond the individual and may involve the interests of communities, societies or other defined groups"). The TCPS also specifically refers to physical and non-physical risks to the researchers. Although the TCPS does state that the risk to researchers may not be a "formal part of its responsibilities, an REB [IRB] ... may consider referring [its] concerns for review [to] an appropriate body within its institution."

Another example is the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research published developed by the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Research Council, and Universities Australia. Initially published in 2007 and updated in 2018, this document outlines the responsibilities of researchers, institutions, and review bodies to ensure "ethically good human research." For example in Chapter 3.4: Animal-To-Human Xenotransplantation, it states that "HRECs [IRB’s] responsible for approving xenotransplantation research must consider the extent to which risks are unknown in the context of public safety and whether the proposed research should proceed in view of potential unknown risks. An assessment of the risks and benefits associated with xenotransplantation research may be particularly complex due to:

- the potential risk not just to the individual, but also to close contacts and other non-participants;

- the potential for catastrophic harm if an adverse event, such as xenozoonosis, were to eventuate; and

- unknown risks." (Emphasis supplied.)

Consistent with and extending the above considerations, SACHRP supports the notion that IRB review of the harms associated with research that may affect individualswho are not human subjects falls reasonably within its purview.

Limiting the Scope of IRB Review of Risks to Non-subjects

SACHRP recognizes that within the research community IRBs are sometimes faulted for assuming responsibility "for all things ethical" and serving as gatekeepers for matters beyond those related to research ethics and the low "floor" defined by regulation. IRBs sometimes become indirectly responsible for a variety of matters that are tangential to their formal remit, for example, financial conflict of interest, HIPAA privacy committee review, and institutional ethics training, among others. "Mission creep", as it is called, can overly burden the IRB effort, and detract from its primary purpose, and is sometimes viewed as such by researchers. As a result, many organizations have attempted to delineate IRB and non-IRB responsibilities more clearly in order to not overburden the IRB or to provide support to the IRB so that it can comply with its regulatory and ethical responsibilities. Specific examples are discussed in more detail later in this document.

Despite these concerns, SACHRP believes that those involved in human research protection have obligations which should be interpreted in the context of current and evolving public and scientific expectations and ethical standards, especially given the largely static nature of the rules governing IRB review. So, while cognizant of the concern that addressing risks to non-subjects is extra-regulatory and will lead to IRBs assuming a role that is not specifically written into the U.S. regulatory lexicon, this guidance recognizes a need for protection of non-subjects.

Such non-subject risk analysis and action by the IRB however requires a careful balancing of the additional protections against several factors, including "the probability of the harm to the [non-subject], the magnitude of the harm, the benefits of the research (to the subject and society), and the rights at stake." The IRB’s assessment of risk to non-subjects also requires a careful definition of responsibilities to minimize duplicative, unnecessary, and impracticable review. SACHRP therefore takes the position that the IRB’s deliberation should be triggered by different thresholds and distinct characteristics of the risk to the non-subject.

Characteristics of Research Risks and Thresholds

In addition to the nature of a harm, distinct characteristics of risk may help set parameters for IRB responsibilities with regard to non-subjects (Figure 2). As with risks to subjects, risks to non-subjects may be described in terms of (1) probability, or likelihood of occurrence, and (2) magnitude (i.e. extent, severity, or intensity). Also, as with risks to subjects, risks to non-subjects must be (3) reasonably foreseeable, predictable (anticipated), for them to be of relevance to IRB analysis.

- Probability or likelihood of occurrence (i.e., reasonably foreseeable, predictable, or anticipated)

Foreseeable and probable are distinct dimensions. While a risk that is highly probable may be foreseeable, risks that are unlikely or only linked to a speculative series of events, nonetheless, maybe be foreseeable. However, a risk that has not occurred previously, cannot ordinarily be predicted (e.g. from pre-clinical studies or from experience with similar interventions) and is not foreseeable, but may ultimately occur with high frequency.

- Magnitude of the risk (i.e., extent, severity, or intensity)

It seems self-evident that where non-subjects are concerned, IRBs should not routinely consider research related harms that are no more likely or serious than represent the ordinary risks of daily life. In circumstances where informing non-subjects of such low risk "exposure" directly or via the subject is impracticable or introduces unacceptable harm to the subject, this may be judged as unnecessary as well. IRB’s should therefore only focus on greater than minimal risk studies.

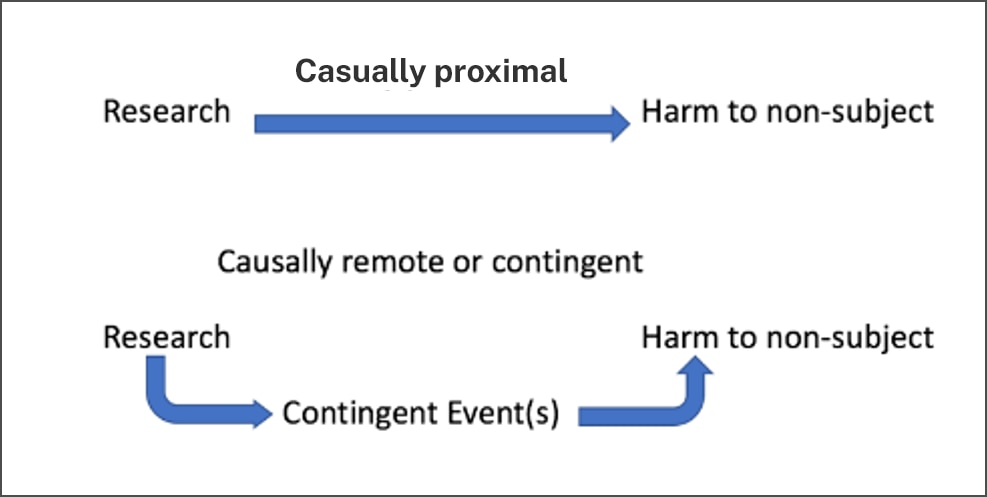

- Causal proximity

One means of identifying which risks of harm to non-subjects matter is the concept of causal proximity (Figure 3), or the degree to which the harm stems directly and immediately from the research, as opposed to being a downstream, secondary, or contingent consequence of the research. Causal proximity describes the relationship between the harm and the research, rather than describing the harm itself. The "possible long-range effects of applying the knowledge gained by the research (e.g., the possible effects of the research on public policy)" fall outside the purview of the IRB because they are speculative and often highly contingent adverse consequences of research. Long-term speculative adverse effects of research on both research participants and communities and groups from which participants were drawn are beyond the scope of IRB consideration, but direct connections between the research and adverse effects on both participants and their communities fall squarely within the IRB’s purview.

For example, the conduct or results of a study of aggression in younger male siblings of adolescents with a record of juvenile offenses could stigmatize family members of any adolescent who has a juvenile record; that would be a direct effect of the research, which could potentially be ameliorated by careful attention to study design and dissemination. The possibility that the results could lead to policy changes making it more likely that families of adolescent offenders could be subjected to increased surveillance by authorities or forced into boot camp-like prevention programs would be speculative, contingent, and outside the IRB’s consideration. Additional examples to illustrate these points are below.

Imagine, for example, that a subject exposed to an infectious agent has some likelihood of infecting others. If the subject has frequent contact in closed spaces (known to transmit the infection) with a family member, that family member (a non-subject) may become seriously ill. In this case, both the family member’s illness (the risk) would be judged to have some measurable likelihood of occurrence (probable), be serious (or of significant magnitude), and be predictable (it is foreseeable). Because the non-subject’s infection is a direct result of the subject’s research participation, we would also say it is causally proximal.

If, on the other hand, as a result of the serious infection, the non-subject receives an off-label treatment which causes a rare and serious toxic reaction, we would not regard this event —the reaction--to be proximally related to the research. The toxicity is a direct effect of the off-label treatment and not of the research (the planned exposure of the subject) itself. An untoward event may be of low probability but causally proximal, or highly probable but causally remote. Consider a study in which an experimental surgical intervention is expected to result in a prolonged recovery time for half of the participants. The prolonged recovery will likely have some untoward effect on all participant’s families, but whether it will cause significant harm in the form of emotional distress, loss of time from work and its consequences, or neglect of other responsibilities and its consequences will depend on family-specific factors and contingencies. Even serious and common but secondary effects of research participation would not be considered "proximal," and we argue later these should be outside the scope of IRB concern. More commonly, in a scenario where research subjects are required to travel long distances for extended periods of time in order to access the research, the IRB should not consider the impact of the displacement on the subject’s family as a research risk.

Similarly, group harm may be causally proximal to the research or may be only an indirect or contingent effect of the research. For example, the publication of psychological autopsy data following a cluster of adolescent suicides may, absent adequate privacy protections, identify communities, families or individuals and reveal sensitive private information, adding stigma to an already burdened group. Anticipating such risks to non-subjects permits the IRB to introduce necessary safeguards. However, when the occurrence of a harm (even one that is foreseeable) depends upon a chain of events, we would consider that harm causally remote. For example, while the suicide study may stigmatize non-subjects, a harm such as the denial of life insurance for the families of the study subjects would be causally remote.

Compared to risk to subjects themselves, there are practical and ethical reasons to limit IRB responsibilities with regard to risks to non-subjects; these characteristics of risk can serve that purpose.

Figure 2. Characteristics of Risks Relevant to IRB Considerations

Figure 3. Causal Proximity

IRB Reliance on other Oversight Mechanisms

Despite SACHRP’s support for the IRB review of the harms associated with research that may affect non-subjects, all research stakeholders (IRB’s, sponsors, institutions, researchers, and the community), are responsible for recognizing and addressing risks to non-subjects. While IRBs may bring unique expertise to the process of identifying and evaluating risks in the context of the broader research protocol, in many circumstances, the limited remit, expertise, and authority of the IRB requires other stakeholders to play a central role in protecting non-subjects from research risk. IRBs should identify or otherwise be cognizant of research risks that affect non-subjects, and in cases where separate institutional and extra-institutional oversight bodies or non-IRB committees offer expertise and requisite authority in the assessment and management of risk to non-subjects, IRBs should rely on those reviews or seek consultation as required or appropriate.

For example, many institutions rely on a radiation safety committee to review research use of radioactive materials and radiation-producing devices. Institutions that conduct research with recombinant or synthetic nucleic acid molecules and other hazardous biological agents establish institutional biosafety committees (IBCs) to ensure that the biological aspects of the research are conducted in a safe manner by assessing worker safety, public health, agricultural and environmental protection. At the federal level, the NIH established the Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee (RAC) in 1974 to review the scientific, safety, and ethical issues related to basic and clinical research involving recombinant or synthetic nucleic acid molecules. Some research networks (e.g., HIV Prevention Trials Network) also utilize community advisory boards (CABs) as a component of the protocol development process. CAB involvement often considers the community impact aspect of proposed research, and CABs work in collaboration with the sponsor and local investigators to address potential concerns prior to study implementation. Similarly, occupational, employee, and student health functions within institutions play a central role in establishing policies and procedures to safeguard and routinely consult with other entities, such as the IRB, when matters of risk to staff or students is at issue.

SACHRP Recommendation

Although all research stakeholders are responsible for recognizing and addressing risks to non-subjects, SACHRP takes the position that the IRB should assume greater responsibility in protecting non-subjects who may be unknowingly exposed to risk and who cannot take self-protective measures or who may be exposed to experiential harms (e.g. the sexual partner of subject testing an investigational barrier contraceptive, stigma associated with the research results, etc.). This responsibility, however, should be limited in scope and based on different thresholds and distinct characteristics of the risk to the non-subject, namely probability, magnitude, and causal proximity. In addition, where separate institutional oversight bodies committees provide expertise and authority in the assessment and management of risk to non-subjects, IRBs should be permitted to fulfill this obligation by relying on those reviews or seeking consultation when required or appropriate

Special Considerations Regarding Risks to Members of the Research Team and Other Personnel

Members of the research team are frequently exposed to risk that generally fall into one of two categories. One type of risk can be categorized as occupational. Biomedical research often exposes members of the research team to risks including biohazardous materials, needle sticks, and exposure to infectious agents. Occupational risks incurred by employees and staff typically fall under the responsibilities of the research institution, and employers are responsible for alerting employees to risks and for communicating safe practice. When these occupational risks are present, the institutional human research protection program or other organizational components such as occupational safety or environmental health are generally responsible for managing these risks, rather than the IRB.

In addition to occupational risk, the research team and other personnel may be exposed to experiential risk -- activities in settings that present social dangers or expose members of the research team to risks such as violence in the context of research activities or research subjects or on topics that may expose the research team to risk (e.g., research on illegal drug use, involvement in gang activities, research conducted in war torn countries, etc.). Like with occupational risks, experiential risks are often managed by the institutional human research protection program or other organizational components, but the IRB may also assess and manage. The role of the IRB in these circumstances may vary depending on the institution and the IRB’s portfolio of work and familiarity with the types of risks that are inherent in proposed research. For example, institutions with graduate programs that require research may rely on the IRB to help determine the risks of the proposed research and work with student-researchers and faculty mentors to develop plans that minimize unnecessary exposure to experiential risks. On the other hand, institutions that routinely conduct research in settings that involve experiential risks to members of the study team may have established processes for identifying and managing this type of risk. In this case, the IRB may weigh in on the management of the risk, but often will rely on other institutional components to manage the risk.

SACHRP Recommendation

Regardless of the type of risk to the research team or other personnel, SACHRP recommends that IRBs be cognizant of risks to personnel and consider engaging the appropriate authorities within the institution to review and manage such risks.

Special Considerations for Collecting Data on Pregnancy and Outcomes of Pregnancy from Research Subjects and Pregnant Partners of Male for Safety Monitoring

While IRBs do consider risks of pregnancy due to the exposure to an investigational product and often recommend measures to reduce this risk that range from disclosure of the risks in consent documents to requirements for highly effective contraceptive methods, utilization of dual methods of contraception, or abstinence from sexual intercourse for the duration of the trial, policies and practices across IRBs vary regarding whether these types of individuals are considered research subjects or non-subjects. There is also inconsistency as to whether the collection of pregnancy outcome data meets the definition of research as defined in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) regulations at 45 CFR part 46. Central to this discussion are the regulations referenced below.

| Language from the Regulations | |

|---|---|

|

HHS |

According to the HHS regulations at 45 CFR 46.102, "human subject" and "research" are defined as follows: (e)(1) Human subject means a living individual about whom an investigator (whether professional or student) conducting research:

|

|

HHS |

In addition to the above, 45 CFR 46, Subpart B (Additional Protections for Pregnant Women, Human Fetuses and Neonates Involved in Research) and 45 CFR 46, Subpart D (Additional Protections for Children Involved as Subjects in Research) may apply. |

|

FDA |

Per 21 CFR part 50, "Human subject" means an individual who is or becomes a participant in research, either as a recipient of the test article or as a control. A subject may be either a healthy human or a patient and a Clinical investigation means any experiment that involves a test article and one or more human subjects and that either is subject to requirements for prior submission to the Food and Drug Administration under section 505(i) or 520(g) of the act, or is not subject to requirements for prior submission to the Food and Drug Administration under these sections of the act, but the results of which are intended to be submitted later to, or held for inspection by, the Food and Drug Administration as part of an application for a research or marketing permit. |

|

HIPAA |

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) at 45 CFR part 164, also may apply for the use and disclosure of Protected Health Information (PHI) that requires that an authorization be obtained for a patient before the person’s Protected Health Information (PHI) can be used or shared. |

For many interventional studies, a sponsor may choose to collect safety data in order to understand the effects of the intervention or investigational product on the following classes of individuals:

- Subject or the subject’s fetus if the subject becomes pregnant during a study;

- subject’s pregnant partner or the fetus of a pregnant partner of the subject; or

- newborn infant of a subject’s pregnant partner.

When data is collected for this reason on a FDA regulated study, whether the collection of data related to a pregnancy including pregnancy outcomes and data about a newborn or child (e.g., from a subject who becomes pregnant during a study but then withdraws from the use of a test article or a pregnant partner of a male subject) is considered part of a "clinical investigation" depends on the specifics of the protocol and may differ in some respects from HHS requirements depending on how those regulations are interpreted. For example, under certain circumstances the FDA does not consider pregnancy data to be part of the clinical investigation that involves use of a test article on a human subject (an individual who is or becomes a participant in research, either as a recipient of the test article or as a control), but would require data to be reported to the FDA as part of safety surveillance activities and an authorization to be obtained before the person’s PHI can be used or shared. However, when such information is collected for a study conducted or supported by HHS under 45 CFR part 46 regardless of whether the research is also subject to FDA requirements outlined in 21 CFR parts 50 and 56, some take the position that per the HHS Common Rule definitions of "human subject" and "research" outlined in 45 CFR 46 subpart A, these activities are part of the research and the classes of individuals referenced above are human subjects because identifiable data is being collected about them as part of the study and the data collected is part of a "systematic investigation designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge." Those arguing that this data collection is "research" note that the data is only being collected because of exposure to an investigational product during a research study, albeit indirectly. Therefore, any data collected for that purpose should be considered human subjects research as defined by the Common Rule. Under these circumstances the IRB approved protocol, consent form, and HIPAA authorization should describe the type and nature of the proposed data collection, and for (pregnant women, fetuses, and neonates), additional conditions per the requirements set forth in 46 CFR part 46, subparts B or D also apply. This position, however, is not held universally.

While there appears to be general agreement that the collection of information about the pregnancy, including the pregnancy outcome and possible effects on the newborn is protected health information (PHI) that requires authorization from the pregnant partner, not all IRB’s consider the pregnant partner or infant to be research subjects under either the FDA or HHS regulations because such activities do not meet the HHS definition of "research" ("a systematic investigation, including research development, testing, and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge") or a "clinical investigation" because the pregnant partner or infant is not a "recipient of the test article" or a "control" in the study (FDA). Further, the argument here is that there are typically no plans by the sponsor to conduct analysis designed to contribute to generalizable knowledge for research purposes. Instead, the data requested by the sponsor is considered more akin to pharmacovigilance or an individual case study rather than a research activity as defined above. This distinction is offered as some IRBs have policies indicating that case studies, individually and in small numbers, are not reviewed as research. In addition, the collection of outcome data on pregnant partners and infants, also would not require the IRB to make a Subpart B or D determination per 45 CFR part 46.

In a situation where a research subject becomes pregnant and data is collected about the pregnancy or its outcome, there is generally universal agreement that they would continue to be human subjects unless the pregnant subject no longer receives the test article and only agrees to data collection regarding the pregnancy and pregnancy outcome. The collection of such data would need to be described in the protocol and consent/authorization form. In addition, the IRB would also be required to make subpart B determinations to collect data about the pregnancy and subpart D to collect data about infants/children resulting from the pregnancy.

SACHRP Recommendation

When a partner of a study subject becomes pregnant and the sponsor and/or research team wish to collect identifiable information about the outcome of the pregnancy, the IRB should at a minimum require permission to contact the individual, and to collect and use the data regardless of whether the pregnant individual is considered a research subject. When the specific protocol requirements are such that the pregnant partner is a research subject under the regulations, then the study must comply with applicable regulatory requirements (e.g., HHS and HIPAA requirements, including subpart B, subpart D, informed consent, and HIPAA authorization requirements).

However, absent other factors, SACHRP does not consider the collection of safety data from a person who becomes pregnant during the course of the pregnant partner’s research participation to be human subject research and does not consider that pregnant individual to fulfill the definition of research subject under HHS or FDA rules.

-

1. Kimmelman J. (2005). Medical research, risk, and bystanders. IRB, 27(4), 1–6.

- back to note 1 2. Battin, M, et al. (2009). The Ethics of Research in Infectious Disease: Experimenting on This Patient, Risking Harm to That One In Battin MP et al (Eds.) The Patient as Victim and Vector: Ethics and Infectious Disease (pp. 164–183). New York: Oxford University Press.

- back to note 2 3. Id.

- back to note 3 4. United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Human Research Protection (OHRP). (2021, Sept. 24). Exploratory Workshop: Review of Third-Party Research Risks: Is There a Role for IRBs? Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/education-and-outreach/exploratory-workshop/2021-workshop/index.html.

- back to note 4 5. Kimmelman (2005).

- back to note 5 6. Resnik, D. B., & Sharp, R. R. (2006). Protecting third parties in human subjects research. IRB, 28(4), 1–7.

- back to note 6 7. International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Hu-man Use. Final Concept Paper M6: Guideline on Virus and Gene Therapy Vector Shedding and Transmission dated 26 August 2009. Endorsed by the Steering Committee on 18 September 2009. Retrieved from https://www.ich.org/page/multidisciplinary-guidelines.

- back to note 7 8. Resnik (2006).

- back to note 8 9. Smalley, J. B., Merritt, M. W., Al-Khatib, S. M., McCall, D., Staman, K. L., & Stepnowsky, C. (2015). Ethical responsibilities toward indirect and collateral participants in pragmatic clinical trials. Clinical trials (London, Eng-land), 12(5), 476–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/1740774515597698.

- back to note 9 10. Kimmelman (2005).

- back to note 10 11. Sterling, R. (2004). Genetic Research among the Havasupai: A Cautionary Tale. American Medical Association Journal of Ethics. Retrieved from https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/genetic-research-among-havasupai-cautionary-tale/2011-02.

- back to note 11 12. OHRP Exploratory Workshop. (2021, September 24).

- back to note 12 13. Ehlers, C. L., Slutske, W. S., Lind, P. A., & Wilhelmsen, K. C. (2007). Association between single nucleotide polymorphisms in the cannabinoid receptor gene (CNR1) and impulsivity in southwest California Indians. Twin research and human genetics: the official journal of the International Society for Twin Studies, 10(6), 805–811. https://doi.org/10.1375/twin.10.6.805.

- back to note 13 14. Foulks E. F. (1989). Misalliances in the Barrow Alcohol Study. American Indian and Alaska native mental health research: journal of the National Center, 2(3), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.0203.1989.7.

- back to note 14 15. Pine, D. S., Coplan, J. D., Wasserman, G. A., Miller, L. S., Fried, J. E., Davies, M., Cooper, T. B., Greenhill, L., Shaffer, D., & Parsons, B. (1997). Neuroendocrine response to fenfluramine challenge in boys. Associations with aggressive behavior and adverse rearing. Archives of general psychiatry, 54(9), 839–846. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830210083010.

- back to note 15 16. Grant, K. (2021). #MedTwitter Slams Study Tying Credit Scores to Surgical Residency Performance. MedPage Today. Retrieved from https://www.medpagetoday.com/special-re-ports/exclusives/96140#:~:text=A%20study%20evaluating%20the%20use,after%20it%20was%20originally%20published.&text=Conversely%2C%20they%20found%20that%20credit,discern%20any%20negative%20performance%20indicators; Berry J. A., Marotta D. A., Savla P., et al. (2021, December 13). Correction: Predictive Value of Credit Score on Surgery Resident and Fellow Academic and Professional Performance. Cureus 13(12): c55. Retreived from https://www.cureus.com/articles/60695-predictive-value-of-credit-score-on-surgery-resident-and-fellow-academic-and-professional-performance/correction/120.

- back to note 16 17. United States Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments. (1994). Retrieved from https://bioethicsarchive.georgetown.edu/achre/.

- back to note 17 18. Yoon, C. K. (1997, May 12). Families Emerge as Silent Victims of Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. The New York Times.

- back to note 18 19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). The U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm.

- back to note 19 20. Lee, S. S., & Grutman, A. J. (2020). Seeking Justice for Victims of the Guatemalan Sexually Transmitted Disease Experiments 1946–1948. Columbia Journal of Gender and Law, 39(2), 54–90. https://doi.org/10.7916/cjgl.v39i2.5700.

- back to note 20 21. Eyal, N., Kimmelman, J., Holtzman, L. G., & Lipsitch, M. (2019). Regulating impact on bystanders in clinical trials: An unsettled frontier. Clinical trials (London, England), 16(5), 450–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/1740774519862783.

- back to note 21